The impasse of French critical sociology: Attempts at a materialist renewal

Publié en

Cet article fait partie de « La mobilisation du droit par les mouvements sociaux et la société civile »

Many significant intellectual developments (Frankfurt School, Bourdieu) continue to assume that workers, social actors, etc. unconsciously reproduce the social structures of capitalism whilst being alienated by them. They are therefore unable to contribute to their emancipation. We argue that in order to consider new forms of social resistance to domination, we need an alternative approach. We argue that Boltanski’s pragmatic sociology, most notably his conception of institutions, and Latour’s own pragmatic standpoint may offer an interesting solution to the question of resistance. However, as productive as they might sound, these two contributions to critical social theory remain also problematic. Boltanski continues to imagine emancipation primarily as a return to some ideal state, while Latour seems to abandon the question of domination. In this paper we will outline our own position as a materialist critique of the established order. This will lead us to ponder towards the political role of sociologists.

Introduction

§1 This article is concerned with the lack of effectiveness of contemporary critical theories in explaining the conditions for social change. These theories, we would argue, continue to rely on a narrow construction of social actors. Indeed, from the Frankfurt School to Bourdieu, many significant intellectual developments have taken place that continue to be based on a key assumption: that individuals (workers, social actors, etc.) unconsciously reproduce the social structures of capitalism whilst being alienated by them. They accept the objective of their existence and no longer seek to rebel against a system that impoverishes not only their work and culture, but also their soul and their creativity. Moreover, they ensure the reproduction of the system by seeking to engage in mass consumption at any cost, or by glorifying the dominant values.

§2 In this paper we aim to show that today, no new critical perspective has emerged out of this negative representation of the world. Indeed, critical works represent ‘man’ living here and now as nothing more than a deeply degraded, contaminated, and denatured human being. What we have is, in fact, a social actor who, in Rousseau’s philosophical tradition, has been corrupted by a civilizing process deeply affected by modernity or capitalism. This view on social actors rests upon an attitude of disgust towards the world.

§3 This approach is widely problematic: it assumes that capitalism or modernity “have robbed” social actors of their original purity and of the consciousness of their alienated condition. In other words, thinkers belonging to the Frankfurt School theorists and those associated with Bourdieu’s critical sociology believe in the existence of a transcendental and ideal subjectivity for social actors that predates modern society. In their understanding, resistance to alienation would consist in recovering this ideal subjectivity. Frankfurt School theorists have fallen into this trap more than once, trying to capture what is at stake by going back to Rousseau’s state of nature and by using concepts such as “false needs”, “false conscience”, “reification”, “instrumental reason” and so on. Correspondingly, Bourdieu argues that social actors are not equipped to identify and criticise their alienation, and he positions sociology as the discipline that will save social actors from the alienation of their habitus, their illusions and their common sense. We would argue that there are problems with these approaches: i. They assume a pristine state of nature that predates the social and in which humans remain unspoiled; ii. The alienated subject is unable to resist his/her condition by him/herself; iii. Resistance would entail a return to unmediated subjectivity and sociality.

§4 In other words, ironically, social actors cannot contribute to their own emancipation and to the process of social change. This denial of the role that social actors could play in their emancipation is unsatisfactory. It cannot account for new forms of social resistance to domination such as those embodied by the animal rights organization, Extinction rebellion, new feminist movements such as Femen, Temporary Autonomous Zone, movements of unemployed people or illegals, etc. These new forms of resistance demand an alternative approach, one which is firmly embedded in sociological questions about the potential for emancipation in social action.

§5 Focusing on debates in French sociology we explore the potential for such an approach in a stepwise way. Firstly, we examine in detail Bourdieu’s position to show, as evoked, that his intellectual stance, shared with the Frankfurt School, is steeped in idealism. Secondly, we identify the key elements of Boltanski’s pragmatic sociology, most notably his conception of institutions, to show how it provides promising tools to examine people’s actions without burdening them with false consciousness or illusions. Thirdly, inspired by the materialist turn suggested in Latour’s pragmatism, we endeavor to show why part of Boltanski’s critical pragmatic sociology nevertheless contains a latent idealism. Latour’s materialist position is a step forward from takes Bourdieu’s aspiration of an illusion-free society and Boltanski’s metacritical methodology. But we also see why the Latourian rejection of the very ideas of critique and domination remains problematic. Thus, in a fourth step, we outline our own critical and materialist stance, articulated in examples of emancipation already nascent here and now in some social movements. As sociologists ourselves we consider the concept of domination to be of a great importance and we offer a critique of the established order. But we do so, by taking actors seriously, following their own discourses and justifications and by drawing attention to their inherent critical potential. However, we argue that we need to take social contingency into account in order to make sense of critical forms of human agency. First, we note the ambivalence of the law regarding both the established order and the attempts of resistance of social actors and, second, we ponder on the political role of sociologists.

Bourdieu’s critique of social action as reproduction

Common sense, ordinary language and false consciousness

§6 At the heart of the French critical school whose figurehead is Bourdieu lies the idea that the dominated and oppressed play an important role in the reproduction of the conditions of their own domination. To this extent, Bourdieu’s sociological program is suffused with the concerns raised by the Frankfurt School, according to which social actors are unable to move beyond false consciousness and processes of reification.

§7 Indeed in Distinction, Bourdieu states:

“There is no doubt in the area of education and culture that the members of the dominated class have the least chance of discovering their objective interest and producing and imposing the problematic most consistent with their interests. Awareness of the economic and social determinants of cultural dispossession in fact varies in almost inverse ratio to cultural dispossession (…). Every hierarchical relationship draws part of the legitimacy that the dominated themselves grant it from a confused perception that is based on the opposition between ‘education’ and ignorance”1.

§8 Bourdieu openly acknowledges the inspiration that he draws from the Frankfurt School and especially from Adorno:

“What the relation to ‘mass’ (and a fortiori ‘elite’) cultural products reproduces, reactivates and reinforces is not (only) the monotony of the production line or office but the social relation which underlies working-class experience of the world, whereby his labor and the product of his labor, opus proprium [owned piece of work]2, present themselves to the worker as opus alienum [alienated piece of work]3, alienated labor. Dispossession is never more totally misrecognized, and therefore tacitly recognized, than when, with progress of automation, economic dispossession is combined with cultural dispossession, which provides the best apparent justification for economic dispossession. Lacking the internalized cultural capital which is the pre-condition for correct appropriation (according to the legitimate definition) of the cultural capital objectified in technical objects, ordinary workers are dominated by the machines and instruments which they serve rather than use, and by those who possess the legitimate i.e., theoretical, means of dominating them”4.

Written some thirty years later, these lines indeed clearly echo Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment:

“The consumers are the workers and salaried employees, the farmers and petty bourgeois. Capitalist production hems them in so tightly, in body and soul, that they unresistingly succumb to whatever is proffered to them. However, just as the ruled have always taken the morality dispensed to them by the rulers more seriously than the rulers themselves, the defrauded masses today cling to the myth of success still more ardently than the successful. They, too, have their aspirations. They insist unwaveringly on the ideology by which they are enslaved”5.

In other words, if mass culture (Hollywood, reality TV, advertising, etc.) imposes its ideology unconsciously and on such a scale, it is because not only the dominated do not possess the cultural capital that would allow them not only to distinguish themselves in relation to the dominant ideology, but also they fail to produce one to their advantage, as dominants do. This is what Bourdieu refers to as symbolic violence:

“[Symbolic violence] is the violence which is exercised upon a social agent with his or her complicity (…). Social agents are knowing agents who, even when they are subjected to determinisms, contribute to producing the efficacy of that which determines them (…). And it is almost always in the ‘fit’ between determinants and the categories of perception that constitute them as such that the effect of domination arises (…). I call misrecognition the fact of recognizing a violence which is wielded precisely inasmuch as one does not perceive it as such. It is through the fact of accepting this set of fundamental, pre-reflexive assumptions[6] that social agents engage by the mere fact of taking the world for granted, of accepting the world as it is, and of finding it natural because their mind is constructed according to cognitive structures that are issued out of the very structures of the world (…). This is why the analysis of the doxic acceptance of the world, due to the immediate agreement of objective structures and cognitive structures, is the true foundation of a realistic theory of domination and politics. Of all forms of ‘hidden persuasion’, the most implacable is the one exerted, quite simply, by the order of things”7.

§8 On an epistemological level, Bourdieu defines sociology as the discipline that, above all else, should reveal the pre-reflexive presuppositions and denounce the dogmatic acceptance of the established order. The sociologist’s task is to challenge common-sense interpretations that are to be found in ordinary language. Just like a mathematician, she has “to point out that formalization can consecrate the self-evidence of common sense rather than condemn it”8. Although he is quoted less frequently by Bourdieu that other Frankfurt theorists, we find also in his work an echo of Marcuse. Inspired principally by Marx and Freud, this other Frankfurt School member develops a perspective in which alienation and repression merge. For example, he makes the distinction between true and false needs:

“Most prevailing needs to relax, to have fun, to behave and consume in accordance with the advertisements, to love and hate what others love and hate, belong to this category of false needs. Such needs have a societal content and function which are determined by external powers over which the individual has no control; the development and satisfaction of these needs is heteronomous (…). In the last analysis, the question of what are true and false needs must be answered by individuals themselves, but only in the last analysis; that is, if and when they are free to give their own answer. As long as they are indoctrinated and manipulated (down to their very instincts), their answer to this question cannot be taken as their own (…)”9.

Every attempt of liberation requires that we become aware of servitude, but this awareness comes up against false needs that individuals fall to recognize as such. In other words, every attempt of liberation should entail substituting all the false consciousness with self-realisation and awareness. As it is observed in consumption practice;

“Free choice among a wide variety of goods and services does not signify freedom if these goods and services sustain social controls over a life of toil and fear – that is, if they sustain alienation. And the spontaneous reproduction of superimposed needs by the individual does not establish autonomy; it only testifies to the efficacy of the controls”10.

§10 Therefore, the individual who rationalizes her/his act of consumption (for instance, the purchase of a gleaming SUV) in terms of freedom, choice, or selection, only mobilizes the pre-reflexive presupposition of the stereotype of ‘freedom’ in order to justify her/his act of purchase through his ordinary language. And the sociologist who would commit to this illusory freedom in order to develop a sociology of consumption would do nothing but become contaminated by a petrified philosophy of the social, rather than assigning a sociological explanation to that very same act. The first thing s/he should have done is to bid farewell to this ordinary explanation that is inherent in common sense, and to examine how this act is nothing but the product of dominant forms and modes of representation inscribed in a “petit bourgeois” habitus. Ordinary language remains “subordinated to practical functions”, the ones that their habitus assigns to them. This is how, in the manner of the first-generation Frankfurt theorists, Bourdieu indicates in Distinction that dominant modes of consumption serve as model for the modes of consumption of the dominated, through their habitus, even though the latter are unaware of it. The petit bourgeois is the “parvenu” whose acts convey the unconscious desire to symbolize tactlessly a social success and to ape the real practices of the dominants (who, in their turn, would probably object to expressing their domination through possession, of an SUV, as they could consider it vulgar and ostentatious).

A sociological account of freedom masked by habitus

§11 Even though they form an oppositional tandem which Bourdieu aspires to get rid of, the use of the conscious/unconscious distinction – which he constantly evokes – is revealing. The distinction is an inherent aspect of his notion of habitus as:

“a system of durable, transposable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures, that is, as principles which generate and organize practices and representations that can be objectively adapted to their outcomes without presupposing a conscious aiming at ends or an express mastery of the operations necessary in order to attain them”11.

§12 The justification that one is likely to make for one’s practice, therefore, comes therefore as additional element in relation to one’s real motives that are located beneath a habitus which can only be brought to light by the sociologist. The only objective reality is beneath the illusory reality over which our habitus, as structuring structures, weaves a desk blotter. “Social science has to reintroduce into the full definition of the object the primary representations of the object (namely that of common sense which sees the SUV object as the embodiment of a freedom [Author’s Note]), which it first had to destroy in order to achieve the ‘objective’ definition”12.

§13 But it only does so when it is protected from “summary and schematic representations” from “ordinary language syntax” which emerge from the habitus (developed in Bourdieu and Wacquant13). Common sense (and its language) must, therefore, be subjected perpetually to sociological suspicion and to arouse a will of “critical rupture with its tangible self-evidences, indisputable at first sight, which strongly tend to give to an illusory representation all the appearances of being grounded in reality”14. Ordinary consciousness is the reifying consciousness, Marcuse’s false consciousness, alienated by the unconscious game of the habitus.

§14 Bourdieu never compromised on the core of his epistemology. In his best-seller The weight of the world, he gave the impression that he was giving social actors a voice, taking it seriously. However, in the conclusion of the book he returned to his usual conviction that “rigorous knowledge almost always presupposes a more or less striking rupture with the evidence of accepted belief – usually identified as common sense” which contaminates also the sociologist’s point of view. If the sociologist does not liberate him/herself from these pre-conceptions, then the danger is that the field will be “vulnerable to preconstructions or to the automatic effects of social mechanisms (…). Only active denunciation of the tacit presuppositions of common sense can counter for the effects of the representations of social reality”15. Bourdieu continues: “I am thinking particularly here of representations in the press and, above all, on television, which are everywhere imposed on the most disadvantaged as the ready-made terms for what they believe to be their experience. Social agents do not innately possess a science of what they do”16. What laypersons mostly do not understand is, of course, the tacit rules that govern their practices unwittingly in their habitus.

§15 Bourdieu’s fiercest opponents understood well that by inviting us, in the manner of Marcuse, to engage into a form of asceticism towards common sense language, he was willing to demonstrate that “rationality can only be defined as a battle that has to be fought over and over again, against pre-scientific mentality and misleading evidence”17.

§16 Scientific sociological language is what can be articulated before being possibly contaminated by a common sense from which it must be protected. It is beneath ill-thought out prejudices and representations which manifest our habitus. The sociologist must dig out the true meaning of social facts which are different from those assigned by ordinary social actors. Bourdieu’s sociology is thought from the depths: correct language is that of the sociologist before being contaminated by this stratum of dirt made of prejudices. Under the rationality (alienated and reified by the habitus) expressed consciously through common sense, Bourdieu says that there exists another value-free rationality which has the power to reveal the unconscious practical rationality of the actor. The Bourdieusian sociologist would be closest to that value-free rationality, a pure subjectivity which is itself free from all myths, common sense, doxic presuppositions, and received ideas. However, this value-free rationality is itself at risk of being contaminated.

§17 Indeed, the habitus, the individualized social, as he liked to remind us, is the condition of any practice or logic, no matter their mutual interaction. In a society in which the dominant ideology belongs to liberalism and consumerism, habitus will lead social actors to reproduce consumerist behaviors. They will justify their practices by mobilizing, for instance, stereotypes of freedom entirely imbued with dominant connotations (I am free to consume, purchase, express my pride of owning such and such a brand or an SUV). Bourdieu’s aim is to establish a critical thought which identifies the process that creates the illusions manifest in common language under the pressure of dominant ideology and its structures of thought, in order to prevent them from contaminating the language of sociological research. As with Marcuse, Adorno, or Horkheimer, only the intellectual has true consciousness, the transcendental consciousness of depths. But this has to be protected.

The liberated social actor and idealism in critical sociology

§18 Bourdieu’s position lies in the postulate that human consciousness is reified, decadent and distorted by petit bourgeois habitus, consumerism or dominant class values in late capitalism. Beyond all this, there is an authentic consciousness and its lost or censored freedom, in sum, an ideal transcendental state to which human beings should be returned.

§19 But how useful is this classical scheme of critical thought in explaining the numerous reactions from citizens against the unprecedented austerity measures, presented as “prudent governance”, that led many populations into the depths of the economic crisis? Arguably it is no longer satisfactory to account for these attempts at emancipation using a framework that privileges constructions of the subject as alienated, tarred with flaws that despoil him/her, pollute him/her, render him/her incapable of real communicative skills and of attaining a state of perfection that only exists in the fantasy of intellectuals.

§20 Thus we need a different approach. In what follows we present suggestions for an alternative paradigm with the potential to untether sociology in general and critical thought in particular, from these pervasive philosophical understandings of the modern subject. This paradigm can be found in French pragmatic sociology and its recent advances, and more notably, in the work of Luc Boltanski.

Luc Boltanski’s Pragmatic Sociology of Critique

How bodiless beings define reality

§21 In this section we will show how Boltanski comes to grips with the tradition of critical thought and achieves to offer a new orientation. According to him, it is crucial, as it has been the case since Marx, to develop a theory that de-constructs domination. Domination is recognized to belong to higher classes, namely those who escape precariousness or the risk of precariousness. The concept of “domination”, as Boltanski explains in On Critique, refers to the ability of defining reality, namely to the ability to make a reality (“that which hangs together”) out of the world (“that which is uncertain”) — in French “ce qu’il en est de ce qui est”)18.

“We can also say, in a different language inspired by law, that the critique of domination concerns the establishment of qualifications that is [...] the operations which indivisibly fix the properties of beings and determine their worth. This work of qualification generally relies on formats or types, invariably combined with descriptions and/or definitions, which are themselves stored in various forms such as regulations, codes, customs, rituals, narratives, emblematic examples, etc.”19.

§22 Boltanski argues that it is the task of institution to define reality. Indeed, no mere individual could defaine “that which hangs together”, because every human being is embodied in a body. This means that every individual is, necessarily located in space and time, and is thus likely to be accused of expressing only his or her point of view and his or her own interpretation of reality. Consequently, the task of saying “that what hangs together” is delegated to institutions, for the simple reason that they are bodiless. It is those institutions that will precisely enact regulations, codes, and rituals that will then enable us to perceive and talk about reality. And it is thanks to these regulations, codes, and rituals enacted and protected by beings who do have a body (the judge, the policeman, civil servants, European Commissioners, etc.), that bodiless beings, such as the State or capitalism, for example, become constitutive of reality. The Foetal Condition uses the example of abortion as a way to penetrate the fundamental problem of defining what is a human being. The State is entrusted with the very delicate task of turning a being from an uncertain state of things into a person. This is achieved by having recourse to biomedicine filled with embodied beings such as doctors who will begin to identify gametes, pre-embryos, embryos, fetuses, viable fetuses (etc.), and which will give an ontological status to this being and then hopefully, also a legal status20.

“[In the case of capitalism, institutional operations are just as necessary to define the properties of things], what transforms them into products or goods and enables the establishment of markets. For supply and demand to be able to coincide, and a market then to be established and operate (more or less), information about goods must be concentrated in prices. But for this process itself to be possible, the goods must previously have been subject to a labor of definition or rather the relations between goods and the words that designate them, or the names given to them, must have been stabilized by a determinate description. This task of fixing reference is what is performed by brands, and, more generally, institutions of normalization (e.g. ISO norms) or quality control, which prevent objects losing their identity in the course of the multiple uses made of them. All these institutions guarantee, as is said in the case of wine, ‘appellations contrôlées’”21.

Stabilizing reality to avoid anxiety

§23 As one can guess, in our democratic liberal democracies, the law plays a key role in the process of stabilization of reality. It helps to take off uncertainty that would threaten social arrangements and anxiety in front of the risk of perpetual change. Without the law and its numerous acts of stabilizing reality, we would have been unable to share beliefs, ideas and conceptions about the world and the things that surround us.

“[The law contributes to making reality] both intelligible and predictable, by preforming chains of causality likely to be activated to interpret the events that occur. Since the law has to establish links between events and entities, it must equip itself with an encyclopedia of entities that it acknowledges as valid. It is in its power [...] to say what is and to associate decisions about what is with value judgements. This is the reason why the law can only be produced by institutions – dependent mostly, in contemporary societies, on the State. Conversely, any device likely to produce the law can be considered an institution. In that sense, we may say that the law is at the same time a semantic instance, in the sense that it fixes characterizations, and the ontological operator par excellence [...]. Legal institutions always comprise representatives, people in charge or spokespersons who are physical persons, ordinary embodied individuals who can represent these entities, speak on their behalf”22.

§24 However, contrary to what the Frankfurt School theory of reification had implied for a long time, capitalism and the State are not the only bodiless beings that enact the symbolic forms of reality. Depending on cultures and societies, there are other bodiless beings such as religious institutions, political parties, ethnic groups, the dead, etc., but also universities. Therefore, for instance, a doctoral seminar is more or less defined symbolically by the university, which, in turn, relies on embodied beings to (re)state “that which makes things hang together” in the academic world. For instance, the university as institution, forces its members to respect a set of tacit norms and regulations that should fulfil a particular purpose and a concrete set of actions in a given situation. However, complaints often arise, when for instance, the state of things does not correspond to the ideal state of things, according to the institution. Let’s take the example of the doctoral seminar. The professor might be caught daydreaming, the doctoral student might mumble during a presentation, other students in the audience might fall asleep, chat, or play with their smartphones. In this context, somebody might complain and rise a legitimate question, on behalf of the institution: ‘Is this what you call a seminar’? Such a statement “is pointing out the fact that the state of things, here and now, does not deserve to be designated as such according to its symbolic form (the symbolic form of the ideal seminar)”23 — even though the individual that embodies the bodiless being, i.e. the professor embodying the university, had said at the beginning of the year that his seminar would be scholarly and scientific.

§34 It is thus the task of the institutions to, literally, institute reality so that everyone agrees on what we are talking about in a given situation. Institutions play a semantic role, which is necessary in order for someone to be able to comprehend but also to refer things in our common world. In this common world, we live in a routine most of the time.

“It is only when hiccups prevent routines from being followed that the institutional dimension of the institution takes priority. This is also to say that ‘institutions’ themselves must continually be subject to a process of re-institutionalization, if they do not want to lose their shape and, as it were, unravel. In the course of these reparative processes, actors or some of them – usually those to restore the (fictional) presence of the bodiless being by recalling the requirement to act in the correct forms, in such a way as to check its dilution”24.

§26 This is, for instance, the case when the Head of a Department or the Laboratory Manager, calls to order once the (above-mentioned) professor of having devalued the form of its seminar. This is another reason why processes of ritualization are crucial to institutions. They enable us to be constantly reminded of that reality is made of and allow us not to worry about the perfect juxtaposition between symbolic forms and the state of things. In this way, for example, a student’s parent will actually feel for his/her child, during graduation, in front of a group of gowned professors. However, if one or some of the latter came to the ceremony wearing a pair of jeans and sports shoes, a little tipsy from an alcoholic lunch, doubt and worry might emerge: are these people really professors? Are we actually at a graduation ceremony? If we really are, shouldn’t my son’s or daughter’s achievement be taken seriously?

The relationship between reality (that which hangs together) and the world (which is uncertain)

§27 In order for us to avoid permanent uncertainty, institutions constantly need confirmation procedures in order select, from the continuous flow of things, that which hangs together, and to keep it stable despite the passage of time. In other words, these procedures, established by representatives that embody the institutions, must fulfil the task of consolidating reality, while confirming of what it constituted in a certain context and in every possible world, or, in other words, sub specie aeternitatis. In order to confirm reality or at least the really pronounced by the institutions, these procedures may as well pass some “tests of truth”. These tests

“strive to deploy in stylized fashion, with a view to consistency and saturation, a certain pre-established state of the relationship between symbolic forms and state of affairs, in such a way as to constantly reconfirm it (…). Repetition plays an essential role here. [Its] only role is to make visible the fact that there is a norm, by deploying it in a sense for its own sake”25.

§28 In this way, if we go back to the above-mentioned example of the graduation ceremony, we may consider that the confirmation procedure that consists in repeating every year the same kind of tests, mobilizing the same objects (official documents, gowns, hats, university emblem, etc.), allows us, on the one hand, to feel that we find ourselves in a real ceremony, and, on the one hand, that graduating people in the room actually embody, from that moment on, what they have been trained to become (doctors, architects, etc.). This is achieved through the simple yet necessary speech act accomplished by the representatives of the institution, and that allows them to be recognized according to their newly acquired status.

§29 It becomes clear that the law plays an even higher institutional role for society than the codes and rituals within the academic community. If we turn to commercial law, for example, an entrepreneur can be convicted in a court of law for unfair market competition because s/he employed workers illegally.

§30 Thus all the controls that companies are subjected to by work inspectors seeking to unearth unofficial work, may also be considered as a set of devices of confirmation procedures. Here it is not only about the law ensuring that welfare costs and other taxes are actually paid by the employers for all of their workers, but also about restating that the world in which we live in, conforms to commercial law and its fundamental principles about free and fair competition. Competition is a norm which, incidentally, has disseminated down into common representations of the world and what we consider to be real. This is the reason why we would not hesitate to question the validity of a race won through cheating, doping or conspiracy. Within a competitive world, confirmation procedures constantly function as reminders of the founding individualistic, and liberal norms in a way that no other reality is possible.

“By covering with the same semantic fabric all the states of affairs whose representation is dramatized, this deployment creates an effect of coherence and closure – of necessity – which satisfies expectations of truth and even saturates them. This coherence makes manifest an underlying intentionality whose strength is imposed even on those who are ignorant of its content or do not grasp its ‘meaning’. Such operations no doubt play an important role in what might be called the maintenance of reality. When they succeed, their effect is not only to make reality accepted. It is to make it loved”26.

§31 What must be pointed out here is the radical contingency of the social world that Luc Boltanski intends to highlight. To this day, critical theory, whether Bourdieu’s, or the first Frankfurt School’s (Marcuse, Adorno, Horkheimer), has always returned to a transcendental level of guaranteed stability (a philosophical or sociological freedom), which enables us to consider the construction of a common world, which gets, however, immediately reified. Besides, it is why one must acknowledge Honneth’s intuition that this transcendentalism, a position that has opened the way to social philosophy, is a new declination of Rousseau’s pacified state of nature27. If there is an original position in On Critique, it is that of a radical uncertainty about reality, about that which hangs together, and that which is valuable about it. It is the task of institutions to give points of reference that make the understanding of a social situation possible, allowing individuals to coordinate their actions while gaining the impression that each situation stands on its own.

The world as a contingent and immanent background to reality

§32 Institutions format reality, which is thus detached from a background into which it cannot be reabsorbed. This background is the world (le monde) according to Boltanski28. Drawing inspiration once again from Wittgenstein, he defines that world as all that is the case, in other words as all that might happen. Through its tests and characterizations, reality wants to establish some permanence in this ever-changing world by choosing what is valuable within it. For instance, the object “PowerPoint projector” could be mobilized in a seminar, but the comic book that can be found in a student’s school bag could not. The object “contract of employment” could be mobilized in the case of an unfair competition trial but the radio on the work site of the firm cannot.

“Contrary to reality, which is open to the object of pictures (particularly statistical ones) claiming an overarching authority, it is immanence itself – what everyone finds herself caught in, immersed in the flux of life, but without necessarily causing the experiences rooted in it to attain the register of speech, still less that of deliberated action”29.

§33 The world is filled with beings who, depending on their relevance within a given situation, can be either ignored, or rejected or re-characterized and integrated to reality in order to confirm it. In short, reality consists of elements extracted away from the world and which will be put through tests of truth by means of categorizations, characterizations, and generalizations.

§34 Thanks to these confirmation procedures, social reality manages to make us think that it is robust and to make actors internalize their inability to change the format of tests. To rephrase this with the vocabulary of On Justification30, reality is robust or “hangs together”31 when instruments of generalization, representation, and categorization (financial, managerial or political statistical) of “what is and what is given as relevant for the collective seem capable of completely covering the field of actual and even potential events”32. Thus, we can conclude that reality is robust or stands either when no event suddenly appears in the public space to disrupt the pre-established harmony between reality and the staging of reality, or when such an event is inappropriate or invisible.

§35 But a reality entirely submissive to a semantic system stabilized by the institutions would make action impossible. This is the reason why reality always contains the potential for criticism. Institutional language is never in a position to prevent the possibility that actors engage in misconduct and in divergent interpretations of what happens. Indeed, instruments, categorizations, and devices that aim at constructing, organizing, and confirming reality are fragile because critique can always draw events from the world that contradict its logic and furnish ingredients for unmasking its “arbitrary” or “hypocritical” character33.

§36 The texture of reality can, therefore, be questioned because a reflexive moment emerges, and raises the question of how to characterize what happens (example: “is that you call a seminar?” or “do you call this crumpled, hand-written, grease-stained paper a contract of employment?”).

Existential criticism: a first pragmatic step away from idealism

§37 There is, however, another type of test that takes us to the very heart of the renewal of critical theory currently carried out in francophone pragmatic sociology. We refer here to the existential criticisms or existential tests that Boltanski sometimes characterizes as “radical”.

“Existential criticism or existential test, “when it ends up being formulated and made public, [it] unmasks the incompleteness of reality and even its consistency, by drawing examples from the flux of life that make its bases unstable and challenges it in such a way as to confront it with the inexhaustible, and hence impossible to totalize, reserve represented by the world”34.

§38 Here, criticism is pragmatic because it draws its strength from a socially constructed world rather than an intellectually purified state of nature beneath things that constitute our daily life. The living world is the concrete world of experiences lived here and now without any background. “Existential tests present themselves as tests of something, even if, in their case, what is tested has not been subject to official qualification or even explicit characterization, capable of being incorporated into the normative formats that sustain reality”35. Something in the world demands to be accomplished but is hampered by the institutions that prevent it from happening. This triggers a form of thwarted satisfaction. There is already something other in the flow of life than what is shaped under the features of the reality that is given to us, and even if that something cannot be said in the language of institutions, we may nonetheless be driven by the desire to see it come into being.

§39 An existential critique would draw attention to alternative worldly wishes and thus would concretely and materially test the sturdiness of the apparatus which structures reality, in much the same way that the Indignados tried to test the system when they occupied Wall Street as one of the key symbols of capitalism and its institutions. We can get an idea of the consequence for attacking the status quo of the economy from the rapidity with which the police expelled the Indignados from Wall Street. As long as a demonstration disturbs only the average citizen, without undermining the devices of domination, that is the procedures that embody reality, the very urge to dominate will remain unchallenged and the desire for change unfulfilled.

§40 What emerges here is a new paradigm that goes beyond the assumption that there is an unspoiled human being underneath its reification through capitalism, the State, modernity, or consumerism. Nobody expects from the sociologist to help social actors return into some state that precedes alienation. On the contrary, the sociologist’s role is to help social actors here and now undertake some action that would be in line with their own wishes. The sociologist is looking for those things in people’s lives that is amenable to reconstruction and also to help them resist the rigidity of the structures that dominate them. This new paradigm, which liberates critique from any form of idealism is pragmatic sociology. Nevertheless, pragmatic sociology has also some serious limitations, principally because, like other transcendent approaches, it confines the sociologist to a position of exteriority as we will see in what follows.

Towards materialism with Bruno Latour

The persistence of an idealist pragmatic stance

§41 Boltanski, inspired by Bourdieu’s critical sociology, argues that we should retain “the possibility, obtained by the stance of exteriority, of challenging reality, of providing the dominated with tools for resisting fragmentation — and this by offering them a picture of the social order and also principles of equivalence on which they gain strength by combining into collectives”36. We are in partial agreement with this ambition. Indeed, he is right to focus on domination, inspired by Bourdieu’s own concerns. But we would argue that in order to do so we need to go beyond the concept of “exteriority”.

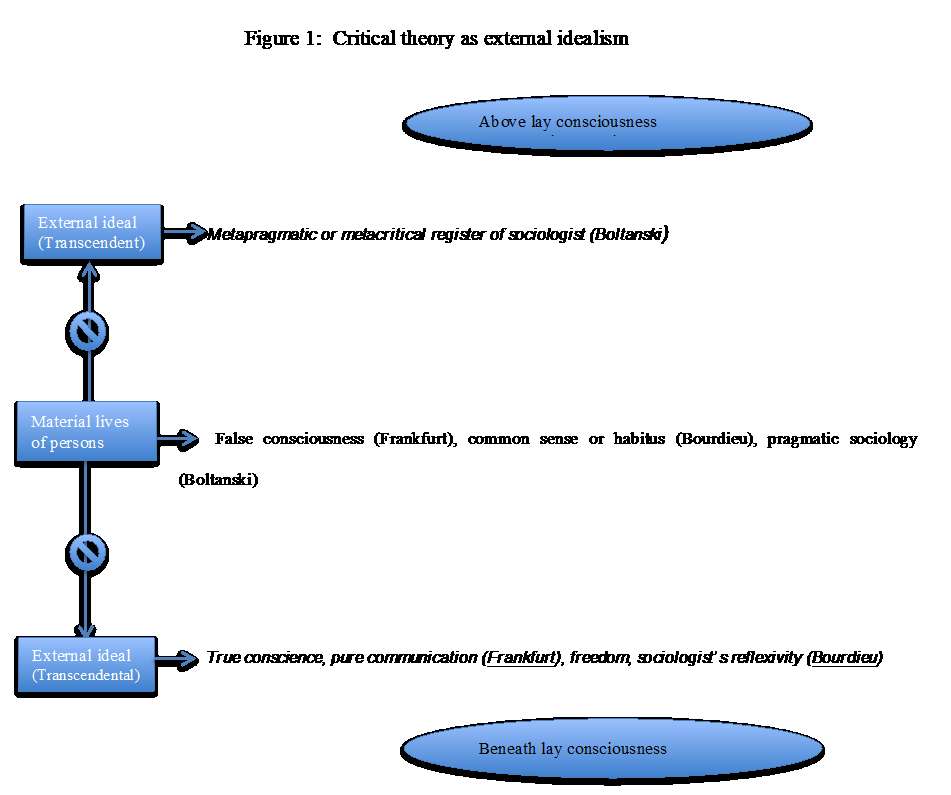

§42 Bourdieu’s aim to examine social action in depth, revealing the free, transcendental subject that is hiding underneath common-sense and illusions, seems to be similar to the aim of numerous Frankfurt School theorists who understood true consciousness as buried inside people’s practical conscience. On this account, Boltanski locates critique on a meta-pragmatic or meta-critical level in order to enable a more detached, synthetic and objective take on the events that constitute reality. People whose margins of action are necessary limited by pragmatic conditions, are therefore confronted to this reality as far as their non-professional reflexivity allows them to. In the process, he privileges a stance that is based on people’s consciousness (transcendent) rather than beneath it (transcendental). Either way, this stance appears to take the form of an ideal, external and inaccessible to these social actors. The positions described thus far can be summarized in the pictorial representation shown below:

§43 Whatever stance adopted, transcendent or transcendental, the sociologist’s true relationship with the world of social actors has to be on the outside. The same sociologist has already taken his/her distance through his/her habitus thanks to the work of reflexivity which freed him from common-sense (Bourdieu, Frankfurt) and the mire of reality (Boltanski).

§44 We have used “No Entry” symbols to show that social actors are stuck in their material lives. On the one hand they do not have access to true consciousness or reflexivity. On the other hand, they are denied the possibility to take a step back from the context in which they live their material lives.

§45 The latter position is held by Boltanski when he uses the term “complex exteriority”, as a way to describe lived situations. To be sure, elsewhere he states that critical sociology can dig out instances of events within the world that are at odds with the official version of reality37. But he turns away from looking into the world for concrete examples of actions which could also challenge this reality so potent and organized. His focus is on how a metacritique can help unravel reality, stripping it of the messiness in which people are embedded and which fosters their alienation. Hence Boltanski’s pragmatism also turns its gaze more firmly towards an ideal of a purified social actor. In this perspective the sociologist, assumed to have already freed him/herself from it, is the one best placed to unpack the institutional framework which constitutes this reality.

The materialist pragmatism of Bruno Latour and ANT

§46 In direct opposition, we would like to propose a materialist stance. This would consist of working with dominated social actors and explore what in their practices, which though emanating from the material world are not fully articulated, can be linked with those of others to develop collective critical voices that challenge the official version of reality. This materialist position starts from the immanence of the world in line with Latour’s project, Latour whose work is also inscribed in French pragmatic sociology alongside Boltanski’s38, rejects the presence of any ideal posture, whether transcendent or transcendental, that would be external to people’s lived experiences. The sociologist’s role is then to work within the lives of actors in order to describe alongside with them the construction of social reality.

§47 Latour proposes working with ordinary people to map their practices in the network of situations constituting everyday life. That’s why Latour defines this stance as an extension of the Actor Network Theory (ANT) that he developed with Michel Callon39. In a network, a given situation is defined as

“the list, specific in every instance, of the beings that will be said to have been associated, mobilized, enrolled, translated, in order to participate in the situation. There will be as many lists as there are situations. The essence of a situation, as it were, for a ‘network’, the list of the other beings through which it is necessary to pass so that this situation can endure, can be prolonged, maintained, or extended. To trace a network is thus always to reconstitute by a test [40] (…) the antecedents and the consequences, the precursors and the heirs, the ins and outs, as it were, of a being. Or to put it more philosophically, the others through which one has to pass in order to become or remain the same”41.

§48 This has implications on his methodology. Latour advises the apprentice sociologist to restrain their analysis into describing the situations where actors engage together in social action: “what they do to expand, to relate, to compare, to organize is what you have to describe as well. It is not another layer that you would have to add to the ‘mere description’. Don’t try to jump from description to explanations: simply go on with the description*"*42. Latour criticizes the fact that there are dominant institutions such as the State, the World Bank, etc… which would have emerged as the sedimentation of pre-existing powerful institutional entities in stable situations43. In effect these institutions would be both abstract, without any tangible material reality. They would influence social actors without their knowledge. Latour argues that they should be excluded from sociological analysis. The focus on sociological labour should be to describe systematically and make visible the situations in which social actors come together in a society and circulate within a massive network with hazy and undefined boundaries.

The consequences of rejecting critique

§49 The problem with Latour’s vision of the social world is that although networks do exist, he also sees them as interconnected in infinite combinations. Dominant institutions do not exist but small material entities combining to create institutions do exist. The question of domination and power differentials among actors inside networks is not considered44. Latour confidently rejects “the dream of a critical sociology” which, he claims, ‘has run out of steam’45. But he throws the baby out with the bathwater and endows social actors with a tacit will to cooperate to ensure that reality as it is is maintained, as if people were inherently prone to protecting social structures46.

§50 Remaining the same, being faithful to oneself, constantly knitting the myriad connections between people and things to ensure the stability and longevity of a situation are tests of confirmation of one’s reality as it is experienced. Against Latour, we agree with Boltanski that that big and abstract institutions do exit (States, religions, capitalist banking networks…), even if they need material bodies to be incarnated. On the contrary, according to Latour, what only matters is these carnal bodies that are interconnected in a giant network which has to be described on a local level. The established order is not apprehended as a potential order of domination because it simply doesn’t exist. We are all links in a chain. For instance, we are consumers, we are the employees of a supermarket chain that distributes products from suppliers who may live on the other side of the world and engage in practices of social or environmental exploitation on a massive scale. In Latour’s work any critical element would risk to get stuck with endless descriptions of carnal and bodiless beings as well as other things that hold together the institutional framework that makes reality hang together. To return to our example, such a stance this would entail a systematic reconstitution of the connections between clients of the supermarket and open cast mines in Bangladesh who provide jobs at $1 a day, along with a description of shopping trolleys, of the supermarket’s parking space, of the river behind the supermarket and so on.

§51 Although in many other ways radical and innovative, embedded as they are in the material lives of people, Latour’s insights nevertheless appear to demand of researchers that they confine themselves to providing accounts of what binds people and things together, legitimating, rather than criticizing, by identifying and flagging up the institutions that frame reality. For instance, we could highlight is the potential for the legal justification of a supermarket chain for the fact that it offers commodities that come through sub-contracting with open cast mines. Latour’s methodology does not lead to emancipation but drowns the reader in a fountain of details described in all their complexity without questioning the fair or unfair nature of the concepts used in the process. We see for instance, that international institutions, such as the IMF, the WTO or the World Bank, define concepts like “free trade” or “fair trade” but at the same time numerous practices related to these concepts, such as delocalization and social dumping, remain unchallenged. Using Boltanski’s terms, in ANT and Latour’s materialism, it is impossible to critique the way institutions define and frame reality as it emanates from the world because the former incorporates the latter. Descriptions of situations lived by concrete actors (with bodies) suggested by Latour are just tests which confirm reality.

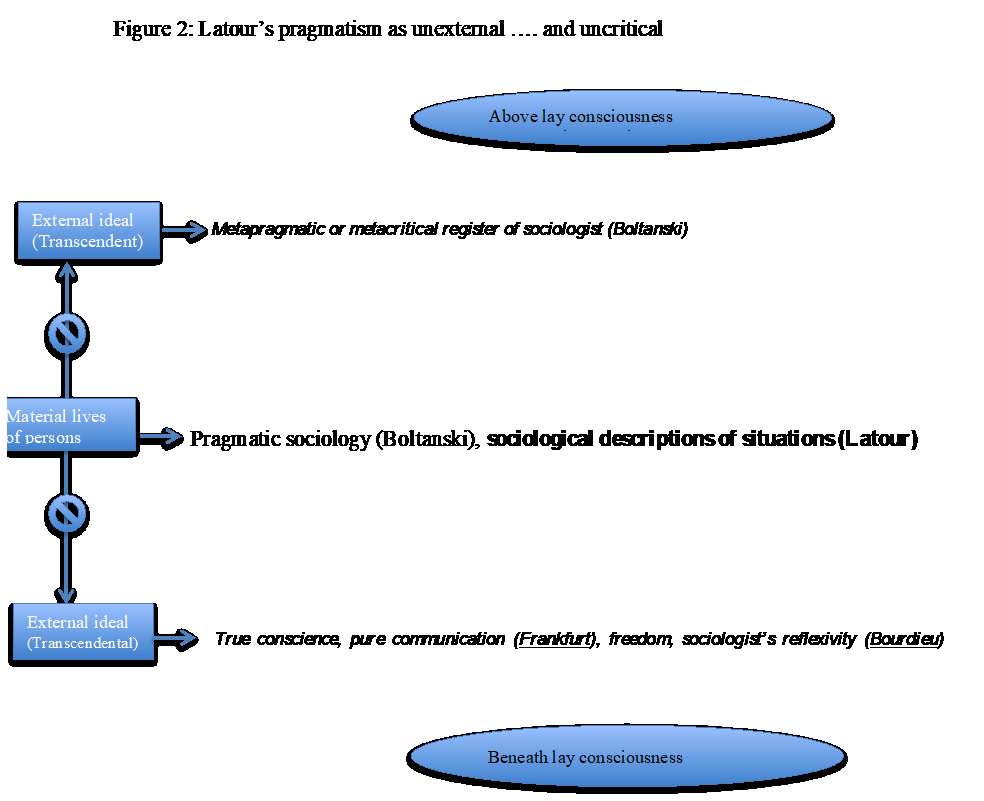

§52 Yet, we would argue that Boltanski’s critique on Latour’s pragmatism has several problems. Indeed, Boltanki’s own response to tests of reality is to advocate the search for new forms of articulation that operate on a level of meta-critique (called meta-pragmatism). To an extent, this entails a return to the classical stance of critical thought that envisions reality from an ideal position. This is shown in the updated Figure 2 below in which we use the No Entry symbols to show that Latour and Boltanski, are both stuck in a framework that does not look for seeds of emancipation within people’s lives. Boltanski finds them in his meta-pragmatic stance. And what is particularly distinctive about Latour’s position is that, whilst he correctly identifies the material lives of persons as the source of sociological analysis, he refuses to move beyond mere description toward critique as we outlined above. Therefore, in what follows we will articulate our own position.

How to be materialist and critical? Diving into emancipatory movements

§53 In response to this stance, we propose to bring critique closer to situations by looking for emancipatory events and desires that challenge the dominant reality in all its constituents. We suggest that we should focus on the actual lived experiences of people in the world; in particular looking for emancipatory events and desires that people express in the flow of everyday life and are noteworthy because they might oppose to the logic of reality (which can be embodied in legal texts or other forms of social normative rules). This critical pragmatic approach does not distinguish between the emancipated (liberated from his/her common sense and illusions) and the alienated, reified actor. Our task should be to those elements in people’s lives that carry some emancipatory potential and which can contribute in the critique of dominant institutions. However, one should be prepared and accept the fact that there is no reassurance as to the possibility to articulate a critical, emancipatory plan, as both the point of view of the sociologist and the point of view of the laypersons are contingent of the world they live in. This is precisely what makes such approach of critical pragmatism firmly materialist.

§54 However, the process of articulating a theory along with the actors in a given situation has to be done without actually endorsing actions that consist in legitimating reality as it is so that it allowing it to continue. It is rather about working with them in order to make their existential experiences noticeable and comprehensible and to identify those tools that would enable them to escape from an alienating reality. It goes without saying that, in this perspective, sociology must support people’s emancipation not only by pointing out the process of alienation and the symbolic violence on is subjected to, but also by describing the possibility of emancipation with all those elements that one has already at hand. This is the reason why sociology must always aim at the world as it is, containing both the suffering and the desires. These desires are to be found in a perfect, pacified, idealized human being but within real life experiences that are to be found in the real world. Everything is already there, within the concrete, material conditions of one’s life and in forms of association (or aggregation as Latour would put it). These forms, although not necessarily articulated, have always existed as a “line of least resistance” in this world47.

§55 We can think for instance about the first homosexual couple that had the courage to reveal their sexuality in public and had to suffer from the legal consequences of their openness. Other contemporary examples are all these initiatives of alternative and solidarity economy which systematically refuse to comply with the local injunctions of economic institutions. The local exchange trading system (associations whose members trade goods and services with a fictive currency, therefore enabling the most deprived to participate) was condemned in 1997 in Foix, in south-west France, for unfair competition48. Structures whose purpose is to support the development of associations and/or cooperatives have seen their subsidy being questioned each year because, rather than working towards the reintegration of the precariat into the conventional labor market (from which they are ejected again a few months later), they enable them to create their own jobs in a collective framework. What matters is to enable workers to find the meaning of what they produce, to become autonomous (in the strictly Marxist sense of the term), in a context where they are likely to be the owners of their own means of production. These attempts are more difficult to implement than simple re-characterization, and they do not figure in the statistics or in the discourses of the European Social Fund work program whose bureaucrats, the carnal embodiments of European institutions, can threaten to cut subsidies if one fails to meet the conditions in relation to integration of the unemployed within the official labor market49. As bodiless beings, European institutions do not possess the language or the legal framework that would enable them to make sense of these initiatives and accept them as legitimate.

§56 We may also think about all these consumer cooperatives such as community-supported agriculture50 which circumvent the controls of the institution called Health and Safety Agency (and its inspectors made of flesh and blood) by directly getting their supply from local farmers to resist the stranglehold of large consumption emporia such as Walmart. Other examples are the Casseurs de pubs who reclaim privatized public spaces, Greenpeace activists who paralyze nuclear waste convoys, the undocumented immigrants and the homeless who squat in empty accommodation without authorization or share out the unsold products thrown out by supermarkets. In all these cases we are in the presence of emancipatory acts that challenge reality, dominant values and common-sense stereotypes without help from sociologists and other intellectuals who are unfairly considered to be the only capable of revealing the structures of domination.

Why laws, people’s critiques and politics are central in critical and materialist sociology

Social movements and the law

§57 In short, we can observe that all these groups are contesting the boundaries of authority and challenge dominant institutions. Very often, these groups use the law in order to force the State to promote social change. The law is a double-edged tool. It does not operate exclusively to sustain dominant institutions and shut down legitimate critiques of power. It also offers the ability to recognize and defend the principle of justice that is inherent in the very existence of a legal framework. Liora Israël has shown how certain groups have challenged dominant cultural norms, using the legal apparatus51.

§58 There are many examples where protestors deliberately incite their arrest in order to use their day in court as an opportunity to articulate their demands. Some historical examples of this practice are the suffragettes, objectors of conscience in the two World Wars or in the Vietnam War or South Africans refusing conscription, Ghandi and his followers in South Africa and India, the Defiance Campaign against segregation in public spaces and the Pass Laws in South Africa, the Civil Rights movement in the US. More contemporary examples include Femen, animal rights campaigners, AIDS campaigners, and so much more. These movements use the law as a blade in order to reshape the contours of reality, i.e. in order to challenge the established order52. These forms of resistance, whilst strenuous, have had some success in forcing the State to adopt new individual and civil rights into the legal framework. The role of the sociologists is therefore to support social actors and contribute in articulating these demands for social change.

§59 A materialist critique or a materialist sociology would apprehend these transgressions as attempts for emancipation. All these groups of activists did not wait for critical theory to challenge the reality for them. They undertook some action by themselves. However, our critical materialist approach treats these attempts as an ethic in action, even if some would say that they suffer from impunity, or that they emerge in an ugly world. Of course, nobody can refuse that our world is imperfect or that very often liberation battles and emancipation attempts go hand in hand with acts of violence or other ethical reductions. Like for example, this man in Salvador (Baha, Brazil) who runs a cooperative restaurant during the day and deals heroin at night. The materialist pragmatic stance does not claim that the world is flawless. On the contrary. It focuses on the world as it is and on real people who live in this very flawed and yet worthy world53.

Enabling people’s critique of reality

§60 This critical approach is distinct as it examines actors’ discontent into its limits. Its objective is to understand people’s critical relation to social reality and to channel it towards emancipation. The sociologist does so, knowing that social actors have already found elements that could enable their emancipation in the real world. The role of critical theory is thus to follow the concerns and the criticisms of ordinary actors and reformulate them in order to expose how unacceptable reality really is. Moreover, it should help “translate” actor’s points of view and desires in a way that it will make their justifications understandable by a larger public. Thus, a cooperative can no longer be dismissed as merely “a bunch of poor people who help each other” or pejoratively described as “self-organized mutual assistance groups that unfairly compete with local SMEs (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises)”. Indeed, sociology can help people detach themselves from dominant reality by suggesting to dissociate necessity from reality and raise doubts about the legitimacy of the matter. To give another example, the sociologist is far from being the only actor who is able to point the finger at how the society of consumption has reified our cultural practices to such an extent that we eventually find all these advertisements that invade our TV screens, our metro stations and our bus stops particularly pleasing. Activists such as Casseurs de pubs who daub the very same advertisements today with the desire to attain another possible world, did not waited for Marcuse, Adorno, Horkheimer or Bourdieu to act in this way. But, the fact that these activists run the risk of being arrested or even attacked by the police is something that must concern modern sociologists.

§61 When that theoretical and sociological thought presents itself as the “main access to the truth” there is always the risk that people’s raw “resources emanating from the world” (from the French: “ressources mondaines”) to engage in acts of critique remain ignored. On the contrary, a critical theory that adopts a materialist perspective does not surrender to the usual pessimism according to which the world is inevitably soaked in misery and doomed to remain the same. It does so, by combining Latour’s understanding of social action as immanent and Boltanski’s apprehension of the social actor as criticizer, as he has shown since Love and Justice as competences54. Indeed, for the last twenty years, French pragmatism, with the exception of Latour’s work, has been highlighting social actor’s critical capacity in their everyday lives55. However, there is something missing: the need to consider the necessary political dimension of critical sociology that need to go beyond idealism. This is the reason why we will now ponder on the political dimension of materialism.

Beyond pragmatisms: the political dimension of materialism

§62 The presence of a political dimension is inherent in a materialist stance as its aim is to work with social actors in order to make visible a theory out of their practices, by exposing how these practices which have the potential to challenge reality as it is. By the same token, it is important to be sensitive to the tendency of institutions to censor all experiences evoked above which might be promising of a new reality. This is really important as the reflexive and critical actor might at any time also perform the world in “ugly” ways, drawing on what Spinoza would have called sad passions rather than happy passions (or desires, like Boltanski). We may, for example, recall the recent murder of a young antifascist militant by skinheads in the middle of Paris in 2013 . It is here that the political reflexivity of the sociologist him/herself is needed.

§63 The pragmatic sociologist’s expertise is gained in a scientific engagement towards the world. But how will s/he distinguish between emancipatory and discriminatory or abusive practices? This claim to expertise is in itself politically charged as it will allow certain practices — those that embody happy passions — to be generalizable as emancipatory social action56. This will depend on the research questions that the sociologist will ask to test the ability of practices to challenge the dominant truth about what reality is. For instance, what are the conditions that enable the person who runs the cooperative restaurant to which we alluded above to be also a dangerous drug dealer at night? The articulation of this question and the answer to it are both politically charged.

§64 What is therefore required is the application of sociological reflexivity, without nonetheless denying social actors’ potential for reflexivity and conscience (or lack thereof) as merely the voice of the dominant ideology whose role would be to appease calm people’s anxieties about the world’s effervescence by legitimating that which hangs together. It is therefore imperative to act out this reflexivity as a democratic impulse57 by accepting that the world is contingent and that social action is messy. Thus, the sociologist’s role should be to identify, record and formalize the skills of laypersons and ordinary social actors wherever they have the potential to bear fruit. Of course, sometimes actors turn a blind eye to the reality to which they contribute, so the sociologist’s other role is not necessarily to give them the opportunity to open their eyes to their subordination. Indeed often they are aware of it58 and sometimes they also engage in practices that will alter that very reality.

§65 For instance, the person who runs the cooperative restaurant cooperative who is also a drug dealer at night, embodies a contradiction between acting out a critique of individualism and capitalism on the one hand and engaging in illegal practices on the other. Confronted to this impure state of the world the sociologist can choose to focus on what it means to practice cooperative economy and collective property in a reality in which the economy is driven by private property and competition.

§66 Only then can people’s capacity for meaningful action be developed, thus eliminating the asymmetry that exists between actors’ beliefs and “illusions” on the one hand and the expert’s “knowledge” of the critical sociologist who would be privy to an “underlying reality” on the other59. This is political action par excellence: the sociologist’s responsibility is to accept that by his/her mentoring, s/he will galvanize or reject certain actions influenced by sad passions. In the case of the former, the sociologist’s duty is thus to understand the processes and circumstances which lead to these sad passions.

§67 The concept of action itself also has to be rescued from the danger that it might lose its meaning by being dismissed as the manifestation of alienation. Yet, action as a choice between different options in an unpredictable world must be countenanced. Thus, the target of sociological theorizing is by definition uncertain: is the guy in his cooperative restaurant creating a new form of solidarity, as yet unarticulated as such by formal institutions? Is he a dangerous Mafioso? Or is he both? In critical materialism, this kind of uncertainty does not disappear. The risk is that it will be reabsorbed by tests of truth60 which will make it legible and understandable (X eventually let go of his utopia of self-managing cooperative, he has recovered a proper sense of reality and accepted a stable job at Walmart). However, it need not necessarily be this way.

§68 It is easy to discount extreme actions, such as those of neo-nazis. More mundanely people can find themselves in the position of adopting the dominant values which have enslaved them, by internalizing them as ideologies or as part of their habitus, sometimes going so far as to ardently desire what alienates them. In this respect, it may seem odd for a so-called critical sociologist to see the relentlessness with which some unemployed people strive to find a job — any job! — that would enable them to reintegrate a sacrosanct labor market — the same market that has repeatedly made clear that it does not want them by directing them towards short-term employment. But these very same people might, at other moments in their lives — or in other situations as Latour would say — stand up to the terrifying power of that reality by giving new interpretations to it.

An informed and optimistic representation of a social actor

§69 Materialism offers a quite optimistic representation of the social actor. More specifically, they can never be depicted as being naïve. Boltanski himself was very clear about this:

“It is the difficulty in breaking free of what (…) we can call the seriality and viscosity of the real – that is, if you like, its excess reality – which discourages critique and not (as is often said) the absence of a ‘project’ or an ‘alternative’ to the present situation. As clearly indicated, for example, by the social history of the labor movement, past revolts have never put off their dramatic expression until an ‘alternative’ is presented to them, drawn up in details, on the model of the literary and philosophical genre called ‘utopia’. On the contrary, it can be said that it is always on the basis of revolt that something like an ‘alternative’ has been able to emerge, not vice versa”61.

§70 Sociology can endorse all these expressions of objection, disapproval or dissent that aim to influence public opinion and government policy. It can do so by helping people put aside their individual fragility and construct a stronger, more collective, and therefore more effective, resistance to the reality. This must be done in knowledge that the social world is in permanent reconstruction and capable to undertake anything and not by considering in advance that it is finite and irreversibly alienated.

§71 The investigation field of this type of materialist and democratic sociology should be emergent associations and innovative social expressions that are to be found in the real world. The idea is to start from the creative potential of social actors as they try to adapt to the reality or as they seek for ways to modify it by putting this reality through a(n existential) test. Unlike the meta-critical approach proposed by Boltanski, we do not consider social actors to be unable to attain a meta-critical register of understanding the structures in which they are captured. In fact, we do recognize the constraining power of these structures but we believe that by limiting social actors in their determinism and sociologists in their meta-criticism we lose from sight the very real ability of social actors to engage in conflicts, to hold debates and to adopt political positions on crucial matters within the world.

§72 Thus we are not denying that reality yields alienation but, ironically, as Boltanski himself put it: “By dint of seeing domination everywhere, the way is paved for those who do not want to see it anywhere”62. Rather, our ambition as sociologists is to go a step forward in exposing and understanding the process of domination. We wish to show how democratic social actors can carve their own pathways toward liberation, in specific situations as Latour would say, and how if they act in a coordinated way they can really challenge the belief that reality is necessarily as it is.

Conclusion: The Upcoming Task of a Critical, Pragmatic and Materialist Sociology

§73 At this time, the ideology of management, with its armada of specialists, technicians, and other experts reinforces the status quo as well as a necessary reality almost in a way of a self-fulfilling prophecy: “we do not have a choice, austerity cannot be avoided, welfare benefits must be reduced, public and social expenditure must be cut, we must rationalize, restart growth, work longer, for lower wages, etc.”. In some of his recent texts63, Boltanski mentions that the need for recognition can lead, albeit with difficulty, to common concerns and partial resistance, that can take the form of individual or small-scale DIY (Do It Yourself). In order to minimize the constraints that weigh on them, actors develop a specific interpretative skillset aimed at identifying spaces of freedom by taking advantage of flaws in systems of control. By doing so, they often act at the limits of legality. These ordinary people, who suffer from the effects of domination (people who are involved in an alternative and solidary economy, illegal immigrants, homeless people, and many others) cannot be deprived of the accuracy of their sense of justice, their freedom, the truth of their interpretations as to what occurs in reality, or of their lucidity. But very often all these people are simply unable to act because of the way the world really works.

§74 Bringing closer sociological work to collectives of precarious individuals, however small they might be, is a pre-condition for being able to see reality as it is, in all its intimacies, and therefore, for taking the first step out of it and for identifying other possible realities that the world has to offer. Sociology’s theoretical work of sociology should consist in identifying the way situations in the world connect to each other, even though they are isolated in different contexts where each person undergoes the constraints of their reality — the landlord’s rights to evict squats, applying standards of competition to cooperatives of consumption or to LETS (Local Exchange Trading System), etc. The cognitive tools that the pragmatic perspective provides must enable this type of actions no matter how different their manifestations might be, because they are in fact reinforce with the same material roots that are to be found in the world (in French: “substrats mondains communs”). This echoes partly what Lefort and Castoriadis’ group Socialisme ou barbarie once sought to do with the disparate actions of workers’ collectives in the 1950s64. In order to do so, however, pragmatic sociology must adopt a materialist perspective that would give sociology a political vocation, rather than keep it confined in the the pursuit of some intellectualist — transcendental or transcendent — idealism.

§75 Borrowing from Latour’s insights, we can say that the world that we must regain through the social actions it gives rise to is not a second facade behind a first one, a face behind a veil, a human nature hidden behind a spoilt human, a mysterious being behind its outward manifestations, a truth behind a lie, an anthropological ideal, a state of nature behind a false consciousness or a habitus.

“These stacks of successive layers, all these veils piled on top of one another like so many petticoats keep your eyes turned in the same direction: they confirm us in our desire to accede to the distant [past or future]65 to the ever more concealed. But it’s not a matter of turning our eyes towards the distant; nor is it a matter of seeing through untruthful appearances to seize the hidden truth, but of bringing our gaze back to the near, yes, to our neighbours, to the present, which is always waiting to be recaptured”66.

§76 The contemporary world with its class inequalities of class, its individualism, its consumerism, can be detestable but at the same time, paradoxically, this is the only one we have. By definition, it is this world, accessible here and now by everybody within this official reality, that we must question, exposing its own language. “To wait until we find ourselves transported miraculously to other times and places in order to speak truly is, by design, to lie”67.

“For how many years has it been, how many centuries, since those professionals, the clerics, found themselves in a contemporary period that they didn’t hate with all their guts? Idols, materialism, the market, modernism, the masses, sex, democracy – everything has horrified them. How would they have found the right words? They wanted to convince a world that they hated with all their soul. They really believed that you couldn’t possibly speak absolute revolution except by first deporting people to other places and other times, supposedly more spiritual”68.

§77 We would go further than Latour however, and argue that the sociological project belongs in the world: in the way people aggregate or associate and in their objectives for imagining a better world, and thus it is from within this world that we must criticize dominant institutions, in particular economic institutions, and their ability to construct social reality often confiding it with material existence. Mere descriptions of networks are not enough. We can, as sociologists, join social actors in their effort to denounce the privileges of the powerful that allow them to culminate power, to dominate and to use institutions on their behalf.

§78 This also forces us to rethink and perhaps reimagine the social role of the sociologist in the world: not as standing somehow outside of the messiness of social life but as fully implicated in the world, deriving his/her expertise not from their own social purity but from the systematic analysis of situations, driven by a desire to work in collaboration with social actors with the aim to find meaningful ways to improve the social conditions in which live. The sociologist is therefore neither naive nor superior, but perhaps privileged to have had the time and space to acquire the tools to deploy the sociological ingenuity69. In this sense we can say that doing sociology is a political act: it is about encouraging a more explicit engagement with the world that could bring substantial improvements in people’s lives, not in some unspecified utopia but here and now, and also about being willing to criticize the institutions that foster power and preserve social inequalities.